For the past six months, the William J. Clinton Presidential Library & Museum has showcased presidential portrayals in film and television as part of a temporary exhibit, which concludes later this month. To mark the occasion, the Library hosted two special discussions. Filmmaker Rod Lurie, known for The Contender and Commander in Chief, provided a behind-the-scenes look at how on-screen presidents shape public perception. Meanwhile, New York Times critic Wesley Morris explored what made American cinema exceptional in the 1990s—particularly 1999, a defining year during the Clinton administration—and its lasting influence on popular culture.

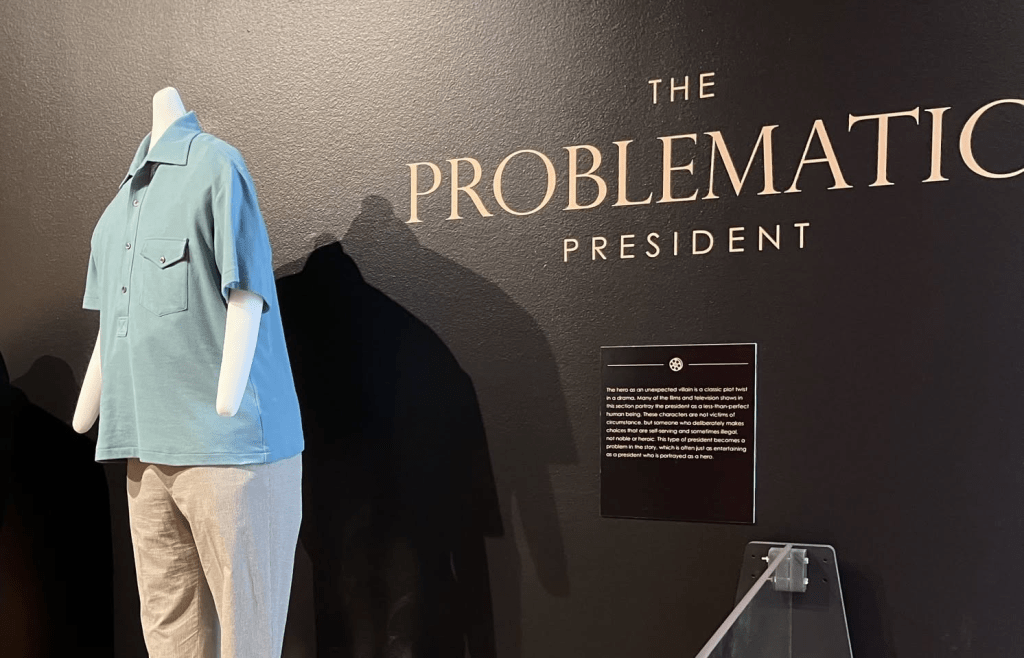

The Library’s exhibit is a must-see for cinephiles, featuring props and costumes from some of the most iconic cinematic presidents of all time. It delves into the portrayal of both fictional and real-life commanders-in-chief as symbols of the nation’s spirit, values, and historical destiny. Over the past century, actors have brought presidents to life in everything from George Washington crossing the Delaware to last year’s controversial The Apprentice, in which Sebastian Stan earned an Oscar nomination for playing the current commander-in-chief. This exhibit covers them all.

Ascending to the third floor of the Clinton Library, you pass the presidential limo and replicas of both the Cabinet Room and the Oval Office—two spaces that have been recreated countless times on screen. The first thing you see upon entering the exhibit is two suits: one blue, one black. The blue suit was worn by Morgan Freeman as President Tom Beck in Deep Impact, as he solemnly informs the world that a meteor is on a collision course with Earth. The black suit belonged to Danny Glover’s President Thomas Wilson in 2012, another leader facing an apocalyptic disaster. Fictional presidents often seem to grapple with threats of staggering magnitude—be it meteors (Armageddon), aliens (Independence Day), vampires (Abraham Lincoln: Vampire Hunter), or even video game characters (Pixels).

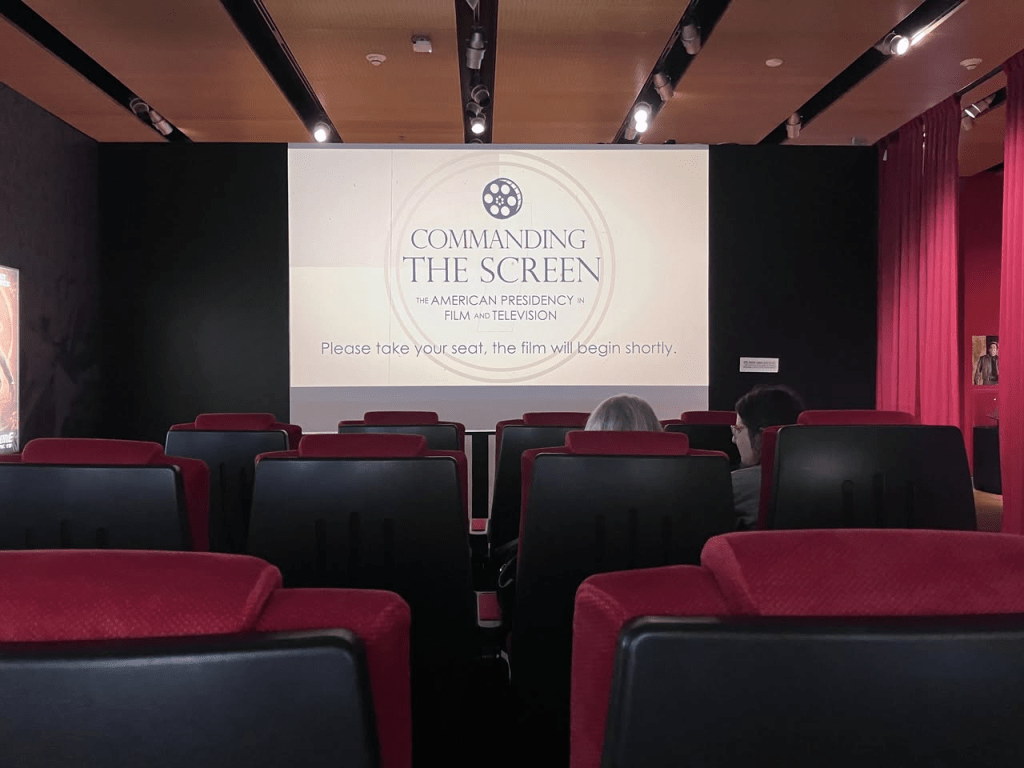

Next, visitors are funneled into a miniature screening room lined with movie posters. Here, you can grab a seat and watch clips from some of the films represented in the exhibit. Jack Nicholson attempts to make peace with CGI aliens in Tim Burton’s Mars Attacks; Julia Louis-Dreyfus delivers her signature brand of awkward wit as the first female president in Veep; and Michael Douglas, as the sitting commander-in-chief in The American President, struggles to order flowers for a date. Many of these films were referenced in the discussions with Lurie and Morris.

The first conversation was hosted by Michael Cook, a political consultant and film critic for KARK and Fox 16. His dual perspective provided fascinating insights at the intersection of politics and cinema. The discussion began with Lurie’s Arkansas connection—his early career as a film critic and his championing of Sling Blade in the ’90s. Lurie recalled hosting Billy Bob Thornton on his radio show:

“I said to Billy Bob, ‘You know you’re gonna win the Oscar for screenplay, right?’ And he goes, ‘I don’t think so.’ I said, ‘I’ll make you a bet. If you don’t win the Academy Award, I’ll do the Billy Bob Got Screwed Hour on my show. But if you win, you gotta thank me at the Oscars.’ And he said we had a deal. I made the same bet with Martin Landau for Ed Wood, Mel Gibson for Braveheart, and James Cameron for Titanic. They all thanked me. Billy Bob screwed me.”

The conversation then shifted to Lurie’s own films, most of which are political in nature. He attributes his interest in politics to his father, who was a political cartoonist. His first two features focused on the presidency, with The Contender exploring the appointment of a female vice president, played by Joan Allen. Her character endures relentless misogynistic scrutiny during her confirmation hearings—something that still resonates today.

“The notion of a female vice president was very important to me,” Lurie explained. “My little girl was about six years old at the time, and George W. Bush had just announced he was running for president. She asked me, ‘Daddy, how come no woman ever runs for president? Why doesn’t Mommy or Grandma run?’ I didn’t have a good answer. Then she said, ‘Well, I’m going to be the first woman president.’ I went downstairs, and a week later, The Contender was written.”

The second discussion of the month was hosted in collaboration with the Arkansas Cinema Society, where Arkansas’s own prolific screenwriter Graham Gordy sat down with film critic Wesley Morris. They started out by listing some of the defining films of the decade—The Matrix, Goodfellas, Pulp Fiction, The Shawshank Redemption, and others. During the ’90s, the man from Hope’s presidency was in full swing, and his policies and scandals were reflected in the shifting culture of the country.

Morris reflected:

“I think the Clinton presidency unleashed something, even before the big scandal. Reagan was a totalizing idea, right? If you look at the values of ’80s movies, it’s quite clear that capitalism is driving the plots. If the plots weren’t about people making money, they were about those people’s kids. It was about deviancy and capitalism as an emotion.”

The shift from the ’80s to the ’90s saw a boom in indie cinema, with filmmakers taking bigger risks and tackling topics like race, sexuality, and war in bolder, more in your face ways.

“The ’90s were crazier, they were wilder, they were more violent. There was a war happening, but there was also something about having a president who had never fought in one. Plus, you had the riots—having the streets move into the cinemas in a way. And I believe that the presidency helps inform what popular culture is, either by being in opposition to that power or in league with it.”

The Clinton Library’s temporary exhibit, Commanding the Screen: The American Presidency in Film and Television, runs through the end of the month. You can watch both discussions with Lurie and Morris on the Clinton Center’s YouTube channel, with more details available on the Library’s official website.

Leave a comment